INSIGHT | 工芸

2019.07.02 16:00

▲ドアから生まれたテーブル(ヤンゴン・グリーン・ファニチャー)と、その上に置かれたフェアトレードの店「ラデー」のリサイクルガラス製品。

▲パラミ通り沿いにあるダッコの店内。

2011年に軍事政権から民政移管されたミャンマー。鎖国状態がなければとっくに失われてしまっていた伝統工芸品が、経済発展とともに洗練されはじめた。海外で学んだミャンマー人や外国人の手によって新しいプロダクトが生まれつつあるのだ。ヤンゴンに旅行しようと思っているあなた、ミャンマーのデザインの最先端に触れたいと思うならこの3つのショップをまわることをおすすめする。

姿を変えるミャンマーの街並み

筆者がこの国を初めて訪れたのは1993年。軍事政権下の辛い時代ではあったものの、当時首都だったヤンゴンは穏やかな田舎町に見えた。ミャンマー式のラぺイエという紅茶を出す喫茶店で談笑する人々。籐などの天然素材でできたテーブルとお風呂場で使う椅子のような低い家具で、膝を突き合わせるように歓談していた。まさに、井戸端、市井の風景だった。あれから四半世紀。軍政から民政移管されたミャンマーの風景は様変わりした。当時目にした籐の椅子は、本当のお風呂場の椅子のようなプラスチック製のものに姿を変え、赤、青、緑といった原色が町に溢れていった。雨季があるミャンマーにとってプラスチックほど便利な素材はない。安くて軽くて、カビが生えにくい。雨季も営業する道端のラぺイエの喫茶店にとって、プラスチックは便利さの象徴だったことだろう。

▲街に溢れるプラスチック椅子と屋台。

イギリス植民地時代に建てられたレンガの建物を除けば、町にはミャンマーの伝統的な木造建築が立ち並んでいた。贅沢なことにこれらの家はチーク材でつくられているではないか。なるほど、耐水性に富み、虫がつきにくい。地元の人の話によると「シロアリはチークの味が嫌いだから食べようとしない」のだそうだ。そのチークの家もヤンゴン中心地からほとんどなくなっている。

▲ヤンゴンの原宿と言われるサンチャウンに、ポツンと残されたチークでできた家。

海外帰国組や外国人から始まった、ものづくりの意識改革

ヤンゴン・グリーン・ファニチャーのデザイナー兼オーナーのクリスティーナ・ウィンは、88年8月8日のいわゆる8888民主化運動の翌年、海外へと脱出したミャンマー人だ。海外とミャンマーの間を行き来しながらも、生活の軸をタイやシンガポールに置き、ジュエリーデザイナーとして活躍してきた。2013年に帰国。そんな彼女を迎えたのが、くだんのプラスチックの椅子の風景だった。

▲ヤンゴン・グリーン・ファニチャーのクリスティーナ・ウィン

海外でデザインを学んできた彼女にとって、便利さ以外に魅力のないプラスチック製品を自分の部屋に置くことなど考えられなかった。そこで、自らのために家具づくりを始める。それは、なくなりつつあるチーク材で建てられた伝統家屋の解体業者探しから始まったという。「ミャンマー人は古いものが嫌いなんです。ですから壊した家の廃材の再利用などはしないのが普通です。新しく家を建てるなら長年使ってきた家具さえも捨てて買い替えてしまうのです」。

ミャンマーでは再利用という発想は嫌われてきたという。解体した家屋のチーク材はおそらく、その価値を知る者の手でひっそりと国外に持ち出されたか、燃やしてしまったのだろう。キズ物を嫌うミャンマー人は虫食いの跡でもあろうものなら、即、薪として火にくべてしまうのだそうだ。現在、都市部ではその価値の見直しはされているのだろうが、地方の場合はわからない。

もちろんこの国にも、チークでつくる家具はある。しかし、それはアジア特有の裕福層が好む重厚さと過剰装飾のものばかり。それが今も変わらず主流だ。ヤンゴン・グリーン・ファニチャーに並ぶ家具は、時を重ねたチークがアンティークの趣を醸し、装飾ではなく木材の「素」を感じさせるデザイン。まだ一般の人たちには受け入れられそうにない。だが、ヤンゴン在住の外国人たちはSNSや口コミで彼女のギャラリーへ早々に集まってきた。

取材時、クリスティーナ・ウィンが主宰する工房では、まさにミャンマー人の嫌う虫食い跡のあるバーカウンターを製作していた。外国人の持ち込みの板で、もともとは大工の作業台だったらしい。工房には集められたドアが多く保管されている。そのドアはあるときは、扉の形をそのまま残しテーブルの天板となる。重みのある天板と軽快なデザインの脚、今昔折衷。海外へ脱出したミャンマー人が、自国の廃品を見事につくり替えた。彼女のようにモノの再生の価値を知る海外帰国組はこれからも増えていくことだろう。

▲虫食いだらけの大工の作業台が存在感のあるカウンターへと再生された。

道端に捨てられたビンから生まれる一輪挿し

クリスティーナの家具のように、雑貨においても再利用の動きが始まっている。ラデーはヤンゴンの中心、道の起点であるスーレーパゴダにほど近いところに店舗を構え、リサイクルとフェアトレードをポリシーとしている店だ。すべてローカルマテリアル&メイド・イン・ミャンマー。店頭にはビニール袋、タイヤ、ガラス瓶などの廃棄品をリサイクルした商品と、各民族の伝統的なテキスタイルの織り柄を生かしたクッションやワンピースが並ぶ。

▲道端のボトルは一輪挿しとなった。

「私は第二次世界大戦終了の8年後に生まれました。当時、祖母がセーターを編んでくれたのです。けれど、子どもの私にはその価値がわからなかった。ナイロンの工業製品のほうがずっと素敵に見えていた」と、ラデーを率いるドイツ人プロデューサー、ウラ・クレーバー。

発展一路のミャンマー。現在、人々はまだ高度成長という欲が犯した環境破壊を実感していない。しかし、世界はエコへと向かっている。ここのガラス製品は、道端に捨てられていたビンのリサイクルだ。ビンは貧困層の人々が集め、アーティストの元へと届け収入を得る。清涼な一輪挿しは道端からやってきたのだ。廃品がデザインという力を借りて収入を生む。

▲ラデーの主宰者ウラ・クレーバーの胸元には紙から再生されたネックレスが。

民族手工芸を現代生活に合わせ、商品化する

ところで、民族の伝統デザインとはどのようなものか。タイとミャンマー国境をまたぐ場所に位置するラフ族の若者に、あなたの民族衣装のデザインの意味を教えてと聞いてみると「きっと、意味があると思います。でも、おばあさんたちに聞くの忘れちゃったなぁ、わかんないなぁ」と話す。彼女が幼少時だった20年前、ラフ族の民族はみな自宅で布を織り、すべて手づくりだったという。祭りのための特別な衣装には銀をしつらえていた。その銀の装飾品は彼女の祖父が火にくべ叩いてつくっていたのを覚えているという。けれど、それを受け継いだ人がいるかどうかはわからない。口承で伝えられる織り柄の意味はわからなくなりつつある。

子犬の牙、カボチャの花など、ミャンマーの織り柄の意味を話してくれたのは和田直子だ。

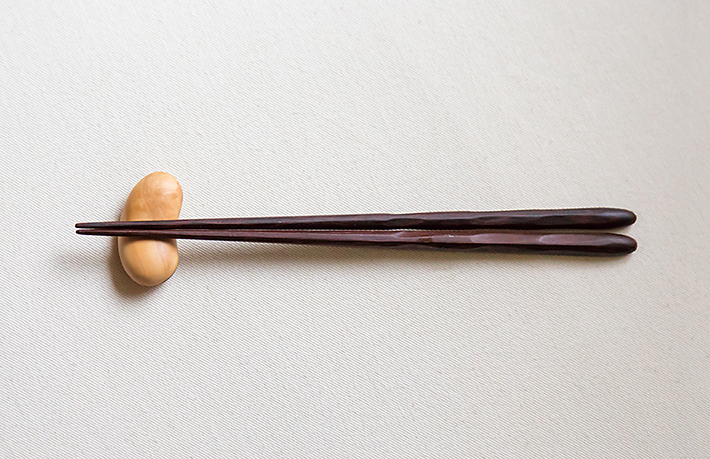

彼女はダッコ(dacco.)というミャンマー人の手によるプロダクトを置く店の経営者で2児の母。NGO職員だった時代に仕事で各地を訪れ、その工芸品に魅せられたのがダッコを始めるきっかけとなった。ミャンマーでも現在、伝統技術の後継者不足が始まっているという。それに歯止めをかけたいとシャン州、カレン州、ラカイン州など20数団体の民族手工芸のプロデュースを手がけている。民族の布を使いネクタイ、ポーチ、トートバッグなどにアレンジしたもの、木工製品でつくる箸置き、アクセサリーなどを売る店は「お土産ならダッコ」と言われるほどになったが、少数民族との共同作業は一筋縄ではいかなかったようだ。

▲ダッコの人気商品であるチーク材でできた箸と箸置き。

「民族手工芸を現代生活に合わせ商品化するということは、ハンドメイドであっても均一のクオリティを必要とします。それに対して、ほつれや小さな汚れぐらいは、いいじゃないかとなかなかハイクオリティの仕上げの要求には応えてもらえなかった」という。常識の違いというほどのギャップがあった。彼らは使う目的に合わせてモノをつくる。使えるモノができれば作業は終了だ。和田はどんな不良品でも買い取ることで少数民族の職人たちとの関係を深めてきた。NGO職員として各地を回った彼女だからできた決断だろう。

▲経営者の和田直子は自ら民族衣装を着て店に立つ。

「少数民族は社会的に閉ざされていたこともあり、自分たちの技術の素晴らしさも価値も知らない」と和田。人件費の安さだけを目当てに大量生産の発注でもあろうものなら、彼らは時短の作業=品質劣化に応じるだろう。自身の成長という意識を目覚めさせるのは難しい。この技術を残し守るのには、正当な対価で取引を行うしかない。1枚のロンジー布を織るのには最低1カ月かかる。根気のいるその作業は経済発展とともに難しくなるのは当たり前だ。しかし、今はまだその手工芸が日常のなかに残っている。この国の手工芸の価値を知る海外との共同作業によって、ミャンマーオリジナルの現代のプロダクトが生まれつつある。(文/能勢理子 写真/兵頭千夏)![]()

Myanmar shifted from a military regime to civilian rule in 2011. Its traditional crafts that would have been lost long ago without its closed state are beginning to be refined together with the country’s economic development.

Here is a report from Yangon on the state of the nation where new products are being born through Burmese who studied abroad and people from other countries.

The changing street scenes of Myanmar

It was in 1993 when I visited Myanmar for the first time. Although it was a harsh era under the military regime, its capital at the time Yangon seemed like a calm countryside town. People were smiling and chatting in tea houses that served a black tea with milk called Rapeie. They were chatting cheerfully sitting close together on low chairs and across low tables made of such natural materials as rattan. Today, a quarter of a century later, the streetscape in Myanmar has changed. The rattan chairs I saw back then have been replaced by plastic ones that seem similar to those used by public baths in Japan, and bright colors such as red, blue, and green flood the city. There is no other material that is more convenient than plastic for Myanmar that has a rainy season. It is light and it is difficult for mold to grow on.

Other than the red brick buildings built during the British colonial period, its streets are lined with Myanmar’s traditional wooden buildings. They are made of teakwood that is a luxurious material in countries like Japan. It makes sense as it is highly water resistant and repels bugs. According to the locals, “termites do not like the taste of teakwood so they don’t eat it.” Most of such teakwood houses have also disappeared from the central areas of Yangon.

Reform in the consciousness in making things started by returnees from overseas and people from other countries

Christina Win who is the owner and designer at Yangon Green Furniture is one of the Burmese who escaped overseas in the year following the so-called 8888 uprising on August 8, 1988. She moved her home ground for living to such countries as Thailand and Singapore where she had been active as a jewelry designer. Win returned to Myanmar in 2013 and what welcomed her was the aforementioned scene with plastic chairs.

For Win who studied design overseas, it was unthinkable to place plastic products that have no other appeal than convenience in her own room. So, she started making her own furniture. She says it started from searching house wreckers of traditional homes made of teakwood that were disappearing. “As Burmese don’t like old things, it was normal to not reuse waste materials from dismantled homes. If they are building a new house, they would even throw away furniture they had been using for years and replace it with new items.”

Myanmar naturally still has furniture made of teakwood, but most of it is hefty and overly ornate pieces that the typical rich Asian stratum is fond of. Furniture seen in Yangon Green Furniture has an antique taste brought by old teakwood, and has designs that give a sense of wood as a basic element that is not decorative. It does not appear it will be accepted by the public yet, but people from overseas living in Yangon have quickly started coming to her gallery after hearing about it through SNS and by word of mouth. At the time of this interview, Win was making a bar counter using materials with worm holes that the locals rather dislike. It originally seemed to be a carpenter’s worktable. Many doors that had been collected were stored in the studio. Those doors will become tabletops while maintaining their shape as doors. A woman who once escaped Myanmar is now brilliantly re-purposing waste material from her own country. Returnees from overseas like Win who know the value of reusing things will perhaps increase from here on.

Single-flower vases made from bottles thrown away in the streets

A movement in reusing materials in daily items is also starting up. HLA DAY is a shop in central Yangon that sets recycling and fair trade as its policy. All of its products use local materials and are made in Myanmar. Products made by recycling waste materials such as plastic bags, tires, glass bottles, cushions, and dresses making use of various tribes’ traditional textile weaving patterns adorn the storefront.

HLA DAY is led by German producer Ulla Kroeber. Its glass products are made by recycling bottles discarded on the streets. The bottles are collected by the needy, and they earn income by delivering them to the artists. The refreshing–looking single-flower vases come the street side. Waste materials are generating income here with the power of design.

Commercializing ethnic handicrafts by designing them to suit modern living

What actually is ethnic traditional design, by the way? When I asked a young La H tribe woman about the meaning of ethnic clothing design, she answered, “I’m sure there is a meaning, but it hasn’t occurred to me to ask my grandmothers, so I’m not sure.” Twenty years ago, when she was an infant, she says all the clothes the La H tribe wore were handmade textiles woven at home. They wove in silver for special costumes worn in festivals. She remembers her grandfather making those silver ornaments by putting silver into fire and hammering it. The meaning of the woven patterns that is handed down orally, however, is being lost.

It was Naoko Wada who taught us the meaning of woven patterns in Myanmar. Wada, who is a mother of two children, runs a shop called “dacco” that sells handcrafted products made by Burmese. She was charmed by the handcrafts while visiting various areas as an NGO staffer, and that prompted her to open dacco. She says a shortage of successors for traditional handicrafts has started in Myanmar as well. Hoping to stop this trend, Wada is producing ethnic handicrafts with over 20 groups in such provinces as Shan, Kayin, and Rakhine. The shop that sells such items as accessories has grown to the extent people say, “Go to dacco if you’re looking for souvenirs,” but Wada says working with minority tribes has not been so easy. She says, “Making ethnic handicraft items to suit modern living requires consistent quality even if they’re handmade. It was quite difficult to get the makers to respond to the demand for high quality finishing, saying minor snags and small stains wouldn’t affect the products.” To them, their work is done once a usable product is completed. By buying up even defected items, Wada deepened relationship of trust with the craftspersons of minority groups.

“As the minority groups have been closed socially, they don’t realize the splendor and value of their skills,” Wada explains. The only way to preserve and protect the skills is to remunerate them with justifiable prices. It takes at least a month to weave a single longyi sheet. It is natural that the painstaking work would be more difficult as economic development advances. Today, however, those handicraft skills still remain in daily living. Myanmar’s original contemporary products are being born through collaborations with overseas groups that are aware of the value of Burmese handicrafts.

Text by Michiko Rico Nose, Photos by Chinatsu Hyodo

本記事はデザイン誌「AXIS」199号「変容する都市」の「ミャンマー、伝統技術をもとにしたモダンデザインの萌芽」を転載したものです。